written by Mike Ryan with research by Doug Heath

How it helped create the Middlesex Fells Reservation and the world’s first metropolitan park system.

The story takes place on both sides of Spot Pond. In 1864, well-known Boston abolitionist Elizur Wright and his family purchased a spacious home in what was then the outskirts of Medford, at the base of Pine Hill on whose summit Wright’s Tower now rises. Today, their home would be under Rte. 93. Alarmed by loggers clear-cutting the extraordinary wildness of the landscape around him, Wright soon launched a public campaign for the entire 4000-acre landscape to become a public forest park. He continued this campaign until his death in 1885.

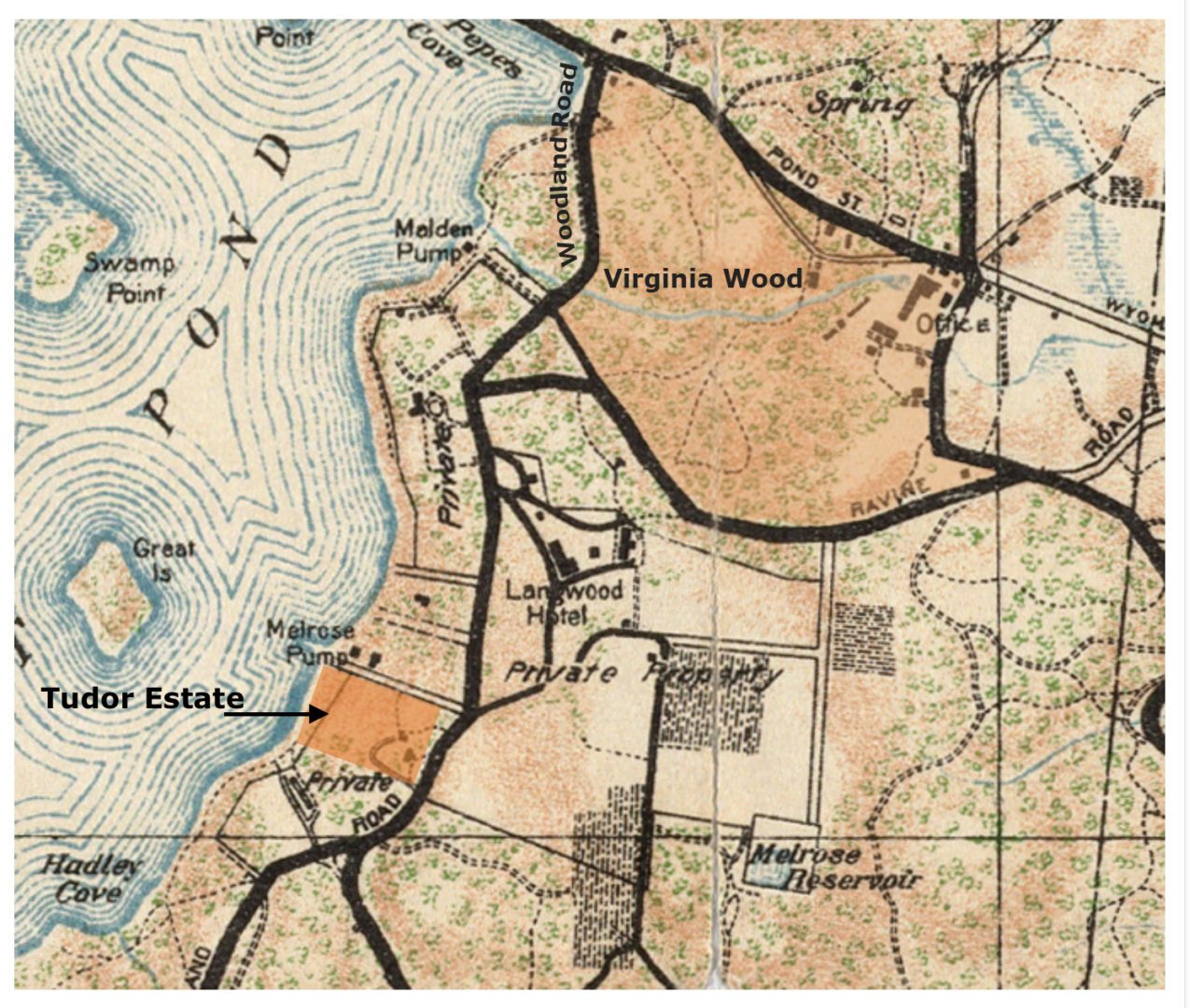

In 1861, three years before the Wright family moved to Medford, William Foster, Jr. of Boston had purchased a stone mansion on the shore of Spot Pond located next to the carriage house we now call the Tudor Barn for his daughter, Fanny Foster Tudor, her daughter Virginia, and husband Henry James Tudor.

This photo taken in 1899 from across Spot Pond shows the mansion where young Virginia Tudor spent time as a teenager between 1862 and 1867. The Tudor Barn is visible to the left with a ramp leading from the mansion to the Barn’s second floor, where a door remains today. Note the lower orchard which was submerged when Spot Pond was raised by nine feet in 1900. The house was demolished sometime between 1912 and 1915, well after the shoreline had been taken by the Metropolitan Water Board as the watershed for Spot Pond, which in 1900 became a drinking water reservoir for the metropolitan area.

The Tudor mansion pictured here was bought in 1861 along with the Tudor Barn by William Foster for his daughter, Fanny Foster Tudor, and her family. His granddaughter Virginia Tudor spent time here until 1867.

The house was built around 1848 from stone quarried just north of Bellevue Pond in the Fells. Today, only the opening in the stone wall for the driveway is visible; the mansion is gone and the slight rise is forested. Virginia, called “Ginny” in family letters, had a garden here and may have sought companions in two nearby mansions or walked along the ravine of Spot Pond Brook.

The Middlesex Fells Campaign

Throughout the 1870’s and early 1880’s, Wright continued to agitate for preserving the Fells as a public reservation. In an 1869 pamphlet, he recommended the citizens of Boston convert the Fells region into a park, “as an attractive retreat into the domain of wild nature herself … and the study of natural history.” He proposed the radical idea of creating railway routes to connect cities to the Fells: “Steam has accomplished, or stands ready to accomplish, this miracle for future ages, that a City Park which is wholly outside of the city, free from its noise and from the dust and smoke of its traffic.”

He was joined in this endeavor by naturalist Wilson Flagg whose 1856 article called for setting aside “a thousand acres or more of wooded land, as near as practicable to every large city, to be kept as a preserve accessible to visitors,” an idea seconded by Henry David Thoreau in an 1859 Journal entry. The Fells today is more than 2,500 land acres.

But Boston’s politicians narrowly voted against spending money on parks outside its city borders. Undeterred, Elizur Wright continued through writings and speeches to gather popular and political support for setting aside the rugged natural beauty he saw in Fells. The movement to save the Fells grew thanks to widespread publicity and organizing throughout Greater Boston greatly assisted by journalist and city planner Sylvester Baxter who wrote extensively for the Fells campaign. In 1880, Wright, naturalist Flagg, Baxter, and others formed the Middlesex Fells Association.

That same year, Flagg wrote three influential articles for saving the Fells as a ‘forest conservancy’ in the Boston Evening Transcript and was instrumental in arranging for F. L. Olmsted’s visit to the Fells with Elizur Wright, which led to Olmsted’s important endorsement of the campaign to preserve the Fells as a forest reservation.

In 1882 the ‘Forest Act’ was passed by the state legislature. As Wright wrote in the Boston Transcript, “The Middlesex Fells agitation has resulted in a…piece of State legislation giving towns and cities the right to take land to be devoted to forestry, on the same terms as for roads or streets.” He later wrote, “Since the passage of the Forest Law, the destiny of the “Middlesex Fells…has become a subject of great interest to the entire commonwealth.”

Nevertheless, at the time of Wright’s death in 1885, the Fells movement had not yet accomplished its mission. But Wright’s campaign for a regional network of larger tracts of public forest land was accelerating.

The next chapter in Wright’s park system vision was about to be written. And while the Tudor family had left their Spot Pond home in 1867, William Foster Jr.’s estate continued to own land near the Pond’s eastern shore in trust for his family.

Trustees of Public Reservations

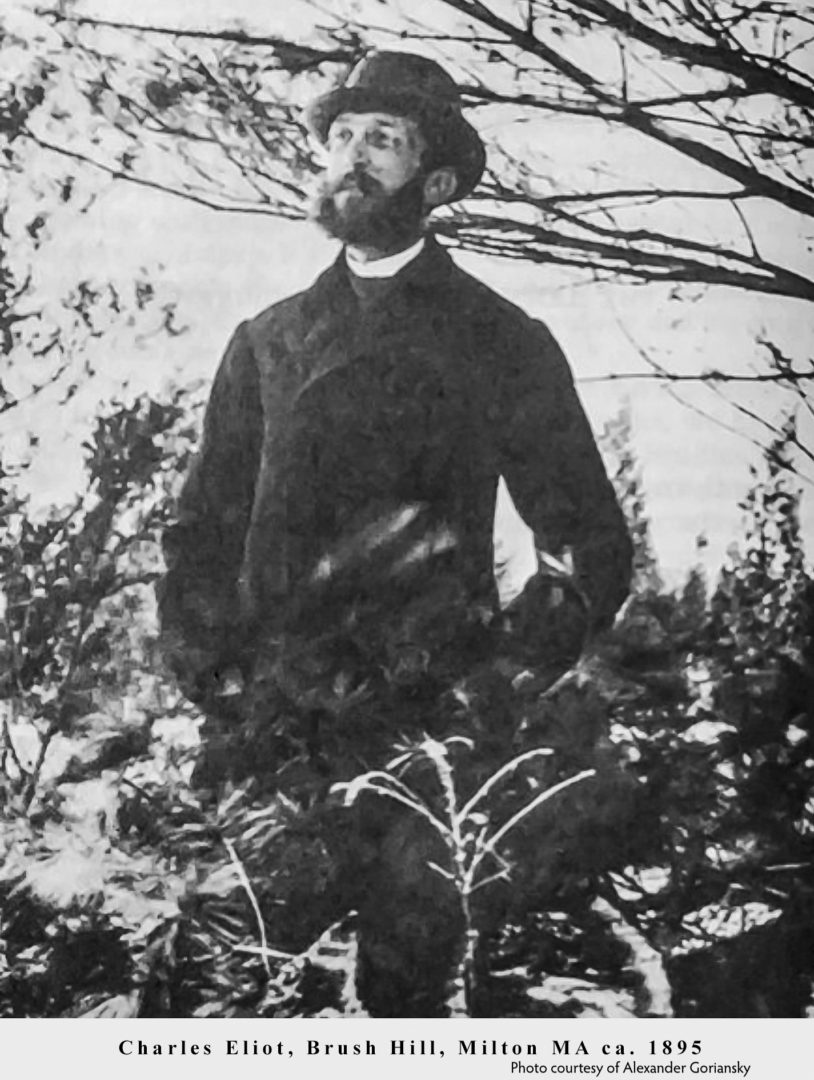

Fast forward to 1886, a year after Elizur Wright died. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s protégé, Charles Eliot, had opened his own firm in Boston. By 1890, by working with Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) leaders, he began to organize support for a plan to create a new kind of institution, a “land trust.” Called the Trustees of Public Reservations, chartered by the Commonwealth, this would acquire beautiful or historical places in any part of the State through gift or purchase. The lands would be held in trust to protect important Massachusetts locations before the forces of development removed them from public access forever.

Soon, activists who had pushed the idea of the Fells as a public reservation joined the organizing committee, encouraged by Frederick Law Olmsted and aided by Medford resident and AMC officer Rosewell Lawrence and Malden resident, journalist and city planner Sylvester Baxter. Strong public support for the goals of the new “Trustees” was said to be due to “public sentiment already in existence” largely formed around the powerful Middlesex Fells campaign, as Eliot’s father later wrote of his son’s career. Following a series of public meetings and State House hearings in May 1891, the charter of the Trustees of Public Reservations was signed into law by the governor, giving the Trustees board the right to accept gifts of property to be managed for use and enjoyment of the public.

By this time, Fanny Foster Tudor was living in Paris across the Atlantic, and may have been aware of the efforts to create the Trustees of Public Reservations and the long-running campaign to set aside the landscape of her former home where her father had invested so much. In 1886 Fanny lost her third and final child, Virginia Tudor, at age 36. With the formation of the Trustees the idea to memorialize Virginia through a gift of land near Spot Pond, where she had lived as a teenager, was born.

Her attorneys in Boston arranged to offer 20 acres along Spot Pond Brook to the brand-new Trustees of Public Reservations. The deed conveyed Virginia Wood to the Trustees “as a natural park for the public benefit,” stipulating that they “maintain the aforesaid designation of said land, ‘Virginia Wood,’ in memory of Virginia Tudor, daughter of Henry J. and Fanny H. Tudor…”

Charles Eliot wrote of the memorial purpose of this generous gift, the first land donated to the Trustees, “Is not a religiously guarded, living landscape a finer monument than any ordinary work in marble or stained glass?”

In 1905, this bronze tablet was embedded high in a stone outcrop in Virginia Wood where it can be found today. Surrounded almost immediately by the newly formed Fells Reservation, Virginia Wood was managed as part of the Fells but not transferred to the state until 1923.

But before the newly hatched Trustees could accept Fanny’s gift they needed to raise enough money to maintain the forest. In December 1891, a total of 158 individuals had contributed $2,000; many were associated with the long campaign to preserve the Fells. But noting the slow pace securing donations for managing private gifts of land into the public domain, the report from the initial meeting of the Trustees Committee stated that urgency required a broader approach in Massachusetts; “the final destruction of the finest remaining bits of scenery goes on more and more rapidly.”

Metropolitan Park Commission Idea

Advocates for the Fells Reservation again came to the fore as Charles Eliot tackled how to manage the first property in the world donated to a land trust. At a September 1891 Trustees committee meeting, a member “broached the subject of the Middlesex Fells and this brought out some suggestions looking toward a metropolitan or State Board possessed of power to condemn lands for public reserves.” Even earlier, at a May, 1890 MIT organizing meeting to create the Trustees, Eliot presciently suggested that a broader state commission would be required: “Someday, perhaps, the State may create a commission and assume the charge of a large number of scattered spots, to be held for the enjoyment of the people. But this day is not yet.”

But that quickly changed.

In November 1891, only six months after the Trustees of Public Reservations was created by Chapter 352 of the Acts of 1891, the Trustees voted to begin galvanizing support “to secure to the public the Middlesex Fells and to consider whether or not it is advisable that a metropolitan park commission be established.” In quick succession the Trustees forged a coalition of regional park commissioners and city officers and launched a petition drive in support of creating a metropolitan park commission. Following a State House public hearing, Eliot drafted legislation for the Metropolitan Park Act which was signed by the governor on June 2, 1892.

The legislation authorized a temporary commission to report on the needs and requirements of a unified park system. Charles Eliot was appointed as Landscape Architect to the Commission, and he selected Sylvester Baxter, the Malden journalist and visionary planner, to serve as Secretary. During the fall of 1892 the new park commissioners engaged in a series of inspection visits to points of scenic interest within 11 miles of Boston. The places they visited were unfamiliar to most of the members, and Baxter wrote that the outings “were like voyages of discovery about home.”

In their 1893 report to the Legislature using detailed maps and surveys, the park commissioners recommended that the state create a system of parks spread over thirty-six municipalities. The report became a best seller with 9,000 copies printed! In June 1893 the Park Act became permanent, new commissioners were appointed, and the way was cleared to realize the vision behind the Fells movement.

On Sunday, March 4, 1894, Boston Herald Readers were greeted with a full-page feature article announcing the creation of the Middlesex Fells Reservation and the Park System. The Herald article informed readers that the creation of the Fells and other great reservations (Blue Hills, Stony Brook, and Beaver Brook) could be directly traced to the educational forces of agitation over many years by leaders of the Middlesex Fells movement. “Of all the tracts whose reservation for recreative purposes has been urged in the course of the past 10 or 15 years, there has been no other whose name has been made so familiar throughout the country.”

One of the first Metropolitan Park Commissioners, William B. De las Casas, wrote an article in 1898 entitled “The Middlesex Fells,” in which he stated that “the efforts made to preserve this region as a public park have given us the entire metropolitan park system.”

It is notable to consider the numerous ways that Fanny Foster Tudor’s Virginia Wood gift to the Trustees as a living memorial in honor of her daughter helped coalesce and advance the drive to create the Middlesex Fells Reservation and the world’s first Metropolitan Park System.

Today’s visitors to the scenic beauty of the Fells Virginia Wood continue to be beneficiaries of the Tudor family’s extraordinary generosity.